Introduction

This post describes three simple demonstration spectrometers that the home experimenter can set up, with a minimum of optical elements, in order to get involved with examining spectra. These optical design demos are able to capture and record the spectrum of any light source. Whether it is a neon lamp, with its characteristic red emission lines, a fluorescent light tube, or any LED lighting around the house that may be of interest to you, these basic designs will not only allow you to see the spectrum, but to record it.

A quick search using the ‘Google Images’ database will hit many of the most common, and not so common, spectrometer designs. Just search for “grating spectrometer designs” or something similar. Many of these schematic drawings are sourced from equipment manufacturers and also from actual scientific journal articles.

The problem is that these descriptions are almost always 2-dimensional. Sometimes they are in 3D which does help. However, in most instances they only display the approximate arrangement of the necessary optical elements. They do not adequately give any idea as to the actual physical size of the final spectrometer, once all components have been installed in some form of light-tight enclosure..

For example, the schematics that we find online never really show the physical size of supports, brackets or similar mountings. Components such as a lens support and holder, a support for an entrance slit, or a support for a grating or prism and a collimator are never really given in detail. Nevertheless, these essential additions to the design all add to the final size of the instrument. and if space and size is at a premium for your particular project, this can be a real issue.

The focal length of the collimator lens, for example, will have a significant effect on size – the greater the focal length, the bigger will be the final “box” required to enclose all these elements. All this is important information that a home experimenter needs to have, when contemplating the construction of a spectrometer.

The purpose of this article, therefore, is to give the reader some idea of what the final dimensions are likely to be for a spectrometer design and how large any light-tight enclosure will be required for housing these components.

Three different optical platforms are described – a prism spectrometer, a transmission grating spectrometer and a reflection grating spectrometer.

Prism Spectrometer

This is the ‘classical’ spectrometer design. You will also see it called a spectroscope, when used visually, or even a spectrograph, which was the usual name when photographic film was the detector. Together with other designs, this classical setup was described in more detail a year or so ago in this article.

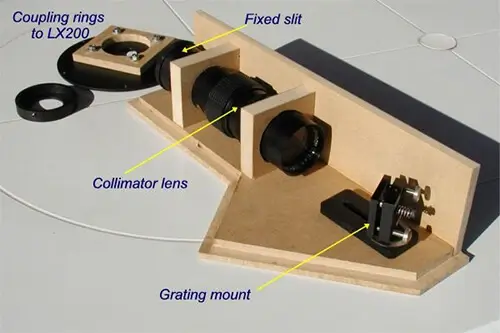

Light rays from a light source, whose spectrum is to be examined, pass through a narrow slit. These rays are then made parallel with a collimator lens of the required focal length. Parallel rays from the collimator are then refracted by a 60° prism before being focused and captured by some form of detector. The obvious choice to focus and record the spectrum is to use a digital camera.

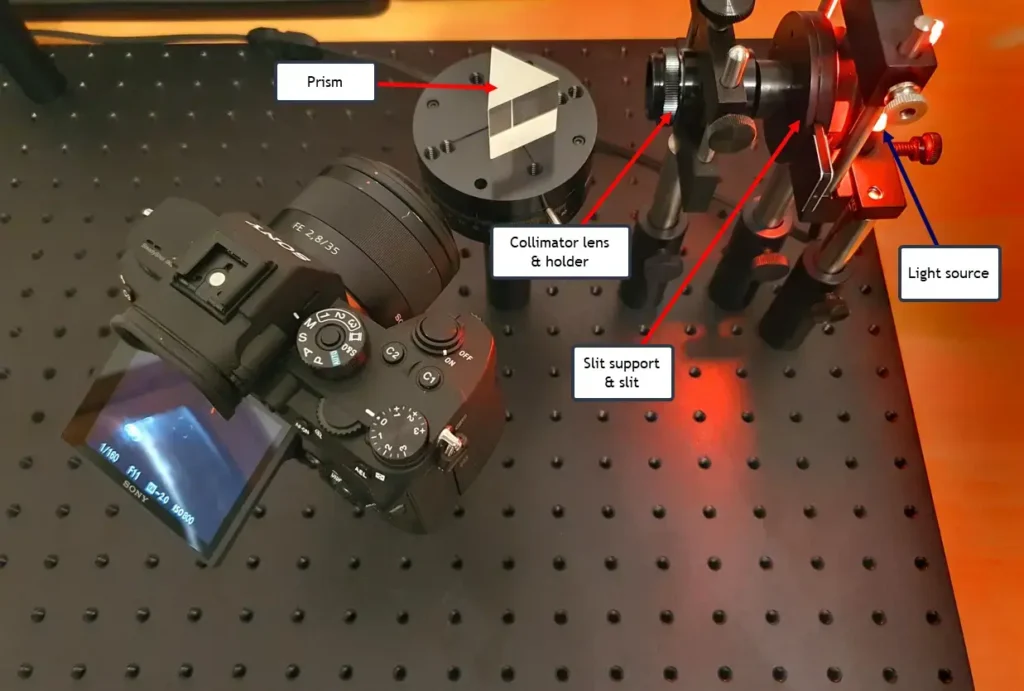

This simple setup can be seen in this image:

The above image uses professional lab components. These can be quite expensive when new, but can be obtained second-hand from the usual auction sites at lower cost. Alternatively, you can easily build a similar setup from much cheaper materials as described below. For stability, all the components are attached to a small optical bench or table (also called an optical breadboard). A base board such as this can itself be home-made. An almost identical optical table that I constructed many years ago is described in this post.

Metal supports and brackets for fixing optical components such as the collimating lens can be made very cheaply using 1 inch (25 mm) right-angled aluminium strip, cut to the required length. This is then screwed or glued onto the base board. A prism or grating, for example, can be held firmly in place on such a strip with double-sided tape. The spectrometer slit itself can be constructed from two pencil sharpener or razor blades fixed together but leaving a very small gap. This can also be attached on angled aluminium in the same way.

A good example using these types of supports and materials for building a Michelson Interferometer is described here.

The optical breadboard above has a matrix of 1-inch holes for reproducibly positioning the various components. So it is a simple matter to estimate what the overall final size of the spectrometer will be. In this example, it is around 16 x 12 inches (40 x 30 cm). Were we to build a light-tight enclosure for this particular design, these dimensions would represent the minimum requirement. The size might be reduced somewhat by using a smaller camera, since this is clearly the largest component.

Reflection Grating Spectrometer

These days spectrometers with reflective diffraction gratings are by far the most common in research labs, in universities and in the field. For manufacturers, the most popular optical design that is marketed today tends to be the Czerny-Turner or the so-called Crossed Czerny-Turner design. The reason for this is a significant reduction in size, especially with the C-T and crossed C-T platforms, that can lead to a compact, often portable, instrument.

For a more complete description of the different types of optical platforms, including the C-T design for spectrometers, this is a useful article.

[Spectrometer designs in the past have been referred to as spectrometer “mountings”. The term mounting can often be found in many of the older scientific papers. The historical significance of the word is explained in this post here. Today, they are usually referred to as optical platforms.]

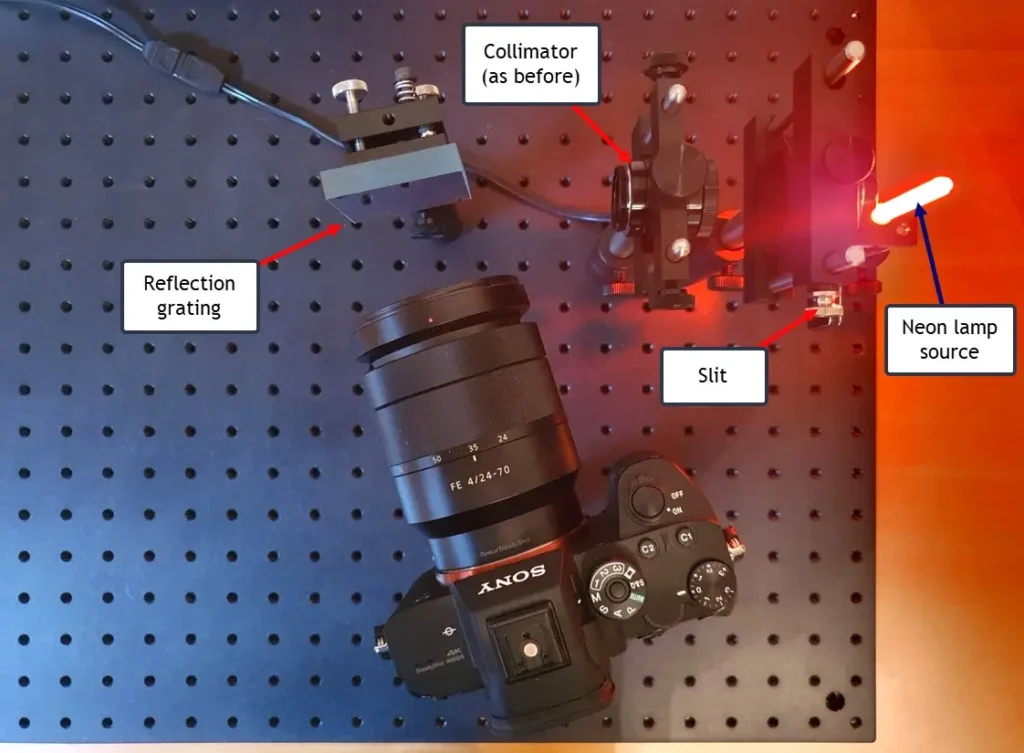

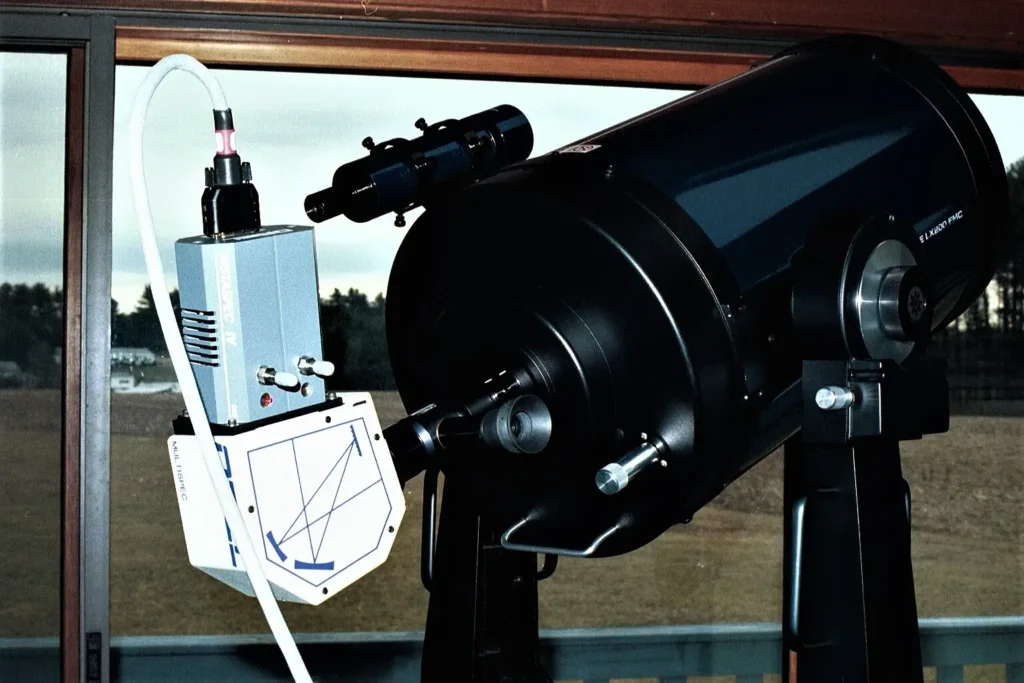

So the next of these demonstration spectrometers can be seen here:

If we “count the holes” again in the base board, we find dimensions of about 16 x 14 inches (40 x 36 cm), slightly larger than the prism case. However, this is largely due to the choice of a much larger 24-70 mm zoom lens attached to the Sony camera for this demonstration. This is a bulky lens and a heavy one – heavier than the camera body!

A more standard 35 or 50 mm fixed focal length lens would produce a much more compact platform. (Note that this is not the Czerny-Turner (C-T) optical design mentioned earlier.) It is, in fact the standard, conventional V-shaped design also in use with reflective grating spectrometers.

Of interest in the image is the large dispersion angle. Light from the collimator strikes the grating at a relatively low acute angle prior to diffraction. This is due to the use of a relatively high resolution (1800 groove per mm) grating and a grating blaze angle that diffracts the light into the first-order spectrum at fairly high diffraction angles.

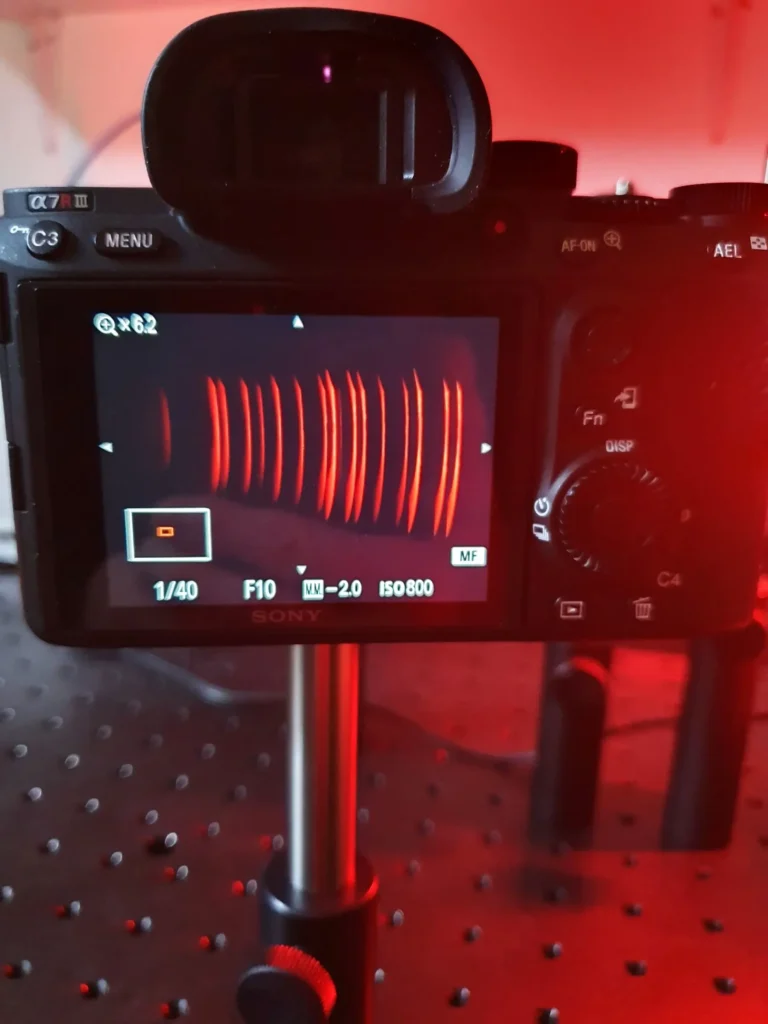

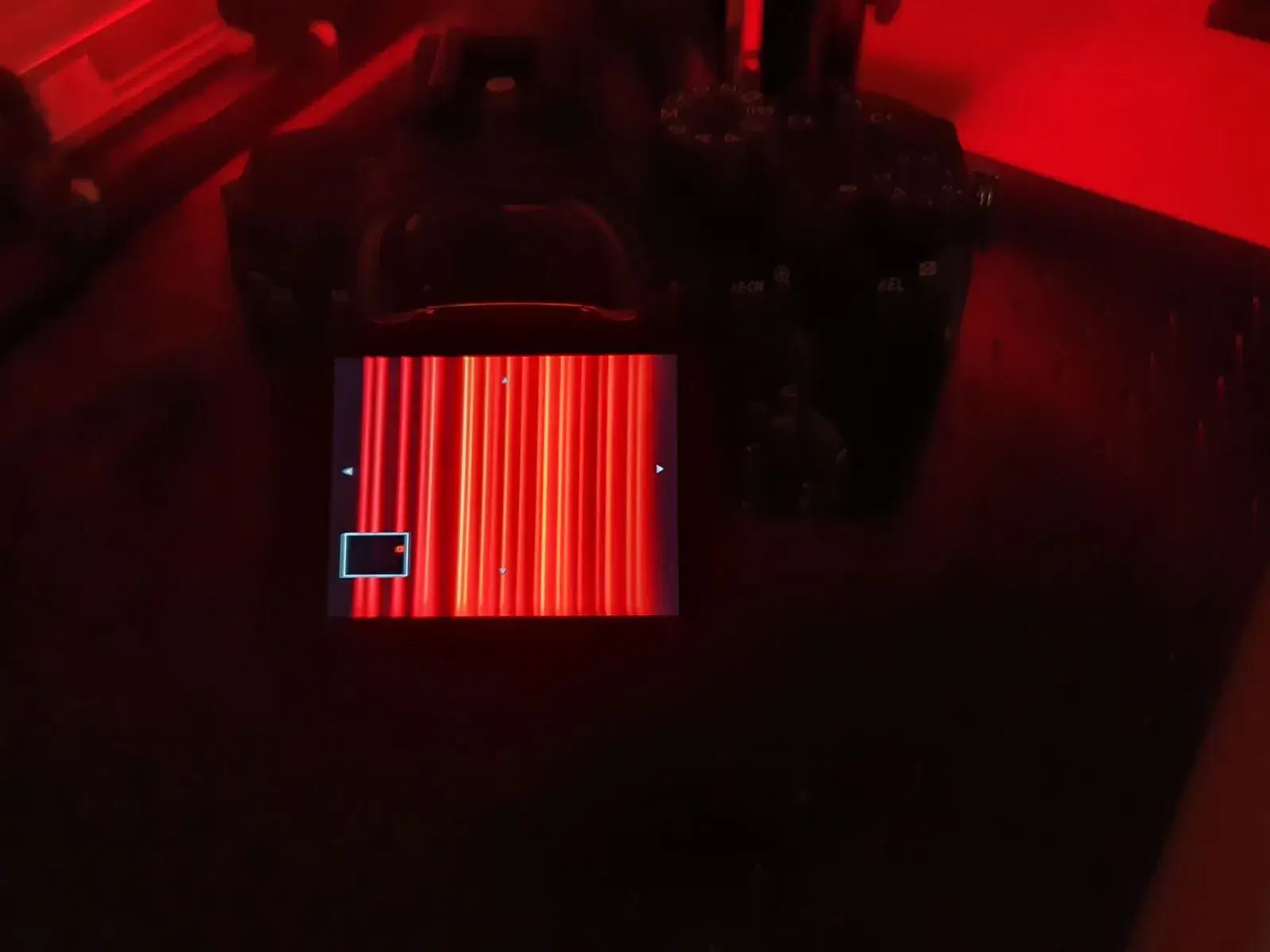

A typical spectrum of a neon lamp with this setup can be here in this close up of the zoomed image taken with a phone camera. Many well resolved red emission lines characteristic of this element are shown:

The Ne lines are slightly curved in this zoomed image, probably from optical aberrations owing to the use of a basic plano-convex lens as the collimator for this simple demonstration. If we were to build a permanent spectrometer according to this design, a fully coated achromatic lens is the preferred option.

Transmission Grating Spectrometer

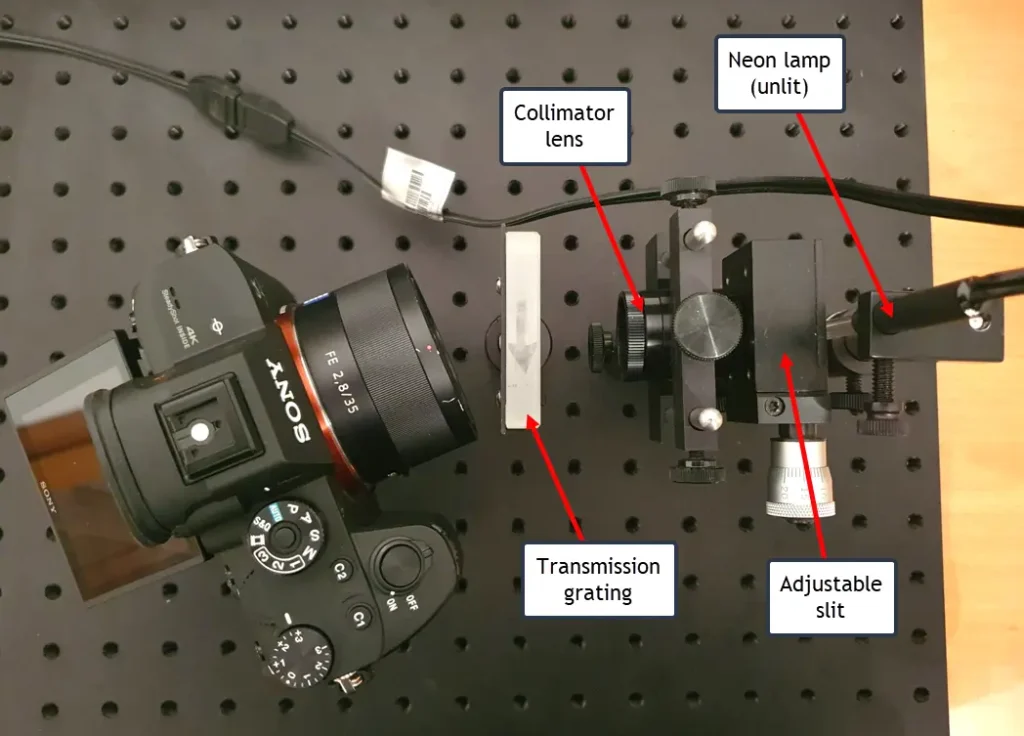

Finally, here is a typical optical platform for a transmission grating spectrometer…

Parallel (i.e. collimated) light from the source is diffracted as before, but this time passes through the grating, hence its name – transmission grating. As a general rule, spectrometers using transmission gratings tend to be physically larger than reflection grating spectrometers.

However, in these “demonstration” platforms we are describing here, when we “count the optical table holes” as explained above, the physical size turns out to be about 14 x 10 inches (46 x 25 cm). This is not too different from the other two designs described above, despite the earlier comment that a transmission grating setup is generally larger than the case for a reflection grating.

The reason for this (of course) is the relatively large size of the digital camera and its focusing lens, which dominates and determines the final size of the platform. It is the common denominator in these 3 designs. A much smaller detector & lens combination, perhaps with a USB connector to a PC to display the captured spectrum, would result in a considerably smaller footprint for the final device. The same comment applies for the first two demos, of course.

However, as a general rule, spectrometers using transmission gratings tend to be somewhat larger, and most certainly longer in dimensions, than their reflective counterparts.

The Next Steps

All of the three design concepts outlined here are able to capture and record a spectrum. A spectrum at this stage is represented as a simple image, most probably in JPEG format, or in some proprietary image format, when we use a digital camera as the detector for our spectrometer.

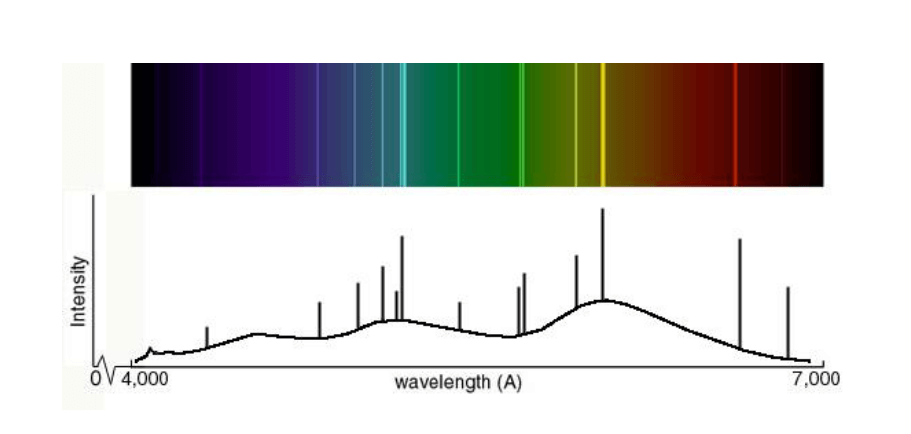

Much more useful for scientific purposes is to create a line profile, which is itself referred to as the ‘spectrum’. This is the form that we see most often in technical publications and online. It is simply created by tracing a horizontal line through the spectrum image at some chosen point. This is then plotted on a graph as intensity versus wavelength, as depicted here in this schematic:

This line profile, when performed correctly with the right software, is an accurate and reproducible representation of the intensity of any absorption or emission line originating from the light source that we are investigating. It ‘becomes’ the spectrum, as we know one today in research labs and elsewhere.

Online software, some of it free and very useful, is available to create line profiles in this way, starting from a spectrum image obtained from a camera. RSpec from Tom Field and Visual Spec, developed by Valerie Desnoux, are two good examples.

And virtually all equipment manufacturers today provide their own software that never really generates a spectral image. This is mainly because commercial spectrometers use what are called linear detectors. These typically have 512, 1024, 2048 or some other binary multiple number of pixels in the horizontal direction, but only 16, 32, 64 or other multiple in the vertical direction. As such, they are perfectly adapted to recording dispersed light coming from a prism or grating in order to produce the spectrum. Therefore they display the data directly as a line profile, which is generally referred to as “the spectrum”.

More information of such linear detectors, as well as other factors that influence the capability of any spectrometer, is described in this post.

If we wanted to go further and explore the details of a spectral line profile, we would need some way to calibrate the spectrum. The original image we capture with a digital camera is obviously in pixels. Once we have the spectral line profile, the graph (or spectrum) that is generated is a plot of intensity (in some arbitrary units) as a function of pixel number.

So we need a means of converting Pixel Number into Wavelength. And this is where spectrum calibration comes in. Without it, all we have are some nice “rainbow” images, perhaps with dark or bright lines or bands that represent the absorption or emission of atomic and molecular species from a light source that we want to examine. These are useful to a degree, but for analysing an unknown source, in absorption or emission, we need to identify spectral lines. And to do this we must perform a calibration.

Light sources used for calibration, and the processes typically employed to calibrate a spectrometer in wavelength units, are respectively described in this earlier post and in this post, which can be read together for better understanding.

Final Words...

To finish, the following gallery of images provide more detail and close-ups of some of the components used in these demonstration spectrometers. Typical spectra from a neon lamp and a mercury lamp are provided. They may assist the interested home experimenter or DIY enthusiast in building your own platform.

- All

- components

- spectra

If anyone has any questions, or is in need of advice and guidance on the choice of optical components, lens focal lengths, or other assistance, please feel free to contact me in English (ou en francais) by leaving a comment on this post, or by using the Contact Form on the site.

Good luck with your own spectrometer design!

Steve

Great article! Spectrometers are handy tools for analyzing material composition in fields like chemistry and astronomy. Thanks for sharing this info!